SHP juniors stepped into the daily realities of those living without stable housing, food security, and consistent incomes as they left campus for San Francisco and San Jose for their annual Urban Plunge during the second week of school. The experience was designed to give juniors “a firsthand account of what it means to serve the marginalized and poor,” according to Mr. Michael Lomas, a part of Campus Ministry and a supervisor to the Plunges. It comes at a time when federal aid programs, such as housing vouchers, food stamps, and Medicaid, are facing proposed cuts under the current administration. The Plunge made many students reevaluate their perceptions of poverty and the implications of those cuts to the vulnerable in our community.

The trip revealed to students the stark inequalities that exist just miles from campus. Charlie Valim ‘27 noted that because “there’s not a lot of empathy” for the unhoused, there is a “general avoidance and disdain for the [impoverished] population.” He found that the Urban Plunge helped him to see that the“wealth disparity is much larger than it should be.”

For students, this awareness came alongside learning about how federal policies have an effect on communities in need. According to PATH Ventures, one of the organizations the juniors worked with, programs like Housing and Urban Development vouchers (HUD vouchers) and nutrition stamps from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) are lifelines for those the juniors met on their trips. And cuts to those programs, according to Mr. Matthew Carroll, a Religious Studies Teacher and another supervisor of the Plunge, will lead to “local nonprofits…being asked to do more with less [resources].”

Carroll also noted that the work requirements that are being newly implemented are “designed to create more accountability, [but] often end up having a counterproductive effect.” For many of those in need, simply “looking for a job to qualify for services” is becoming increasingly difficult, as they spend hours “waiting in line for a meal…because benefits have been pulled, [or] lin[ing] up early to get a shelter spot or bed.” As Carroll put it, “being poor is a full-time job.” At the same time, at PATH, for instance, many residents are unable to work due to disabilities or mental health issues. Stricter federal requirements could strip away the governmental assistance that keeps them alive. Valim noted how the national narrative around homelessness and poverty often misses this reality, and how on certain forms of media, “people [argue] that [some] don’t deserve the aid [they receive] and that we’re only supposed to be giving it to the people in the most need, which they strictly define as people [like] single mothers, and those who are in [extreme poverty].” Whereas in reality, many “poor and unhoused need this kind of aid.”

There is also a moral responsibility that comes with authority. Carroll noted that “authority comes with responsibility, and that responsibility is to promote the common good… particularly the well-being of those who are most vulnerable.” Similarly, Lomas connected such values to Catholic social teaching, adding that we are called to help one another, and just as “Jesus washed the feet of [his] disciples, to prove…that [he is] no greater” than the rest of us, in the same way, “leaders are called to serve the community” and to not distance themselves from the vulnerable.

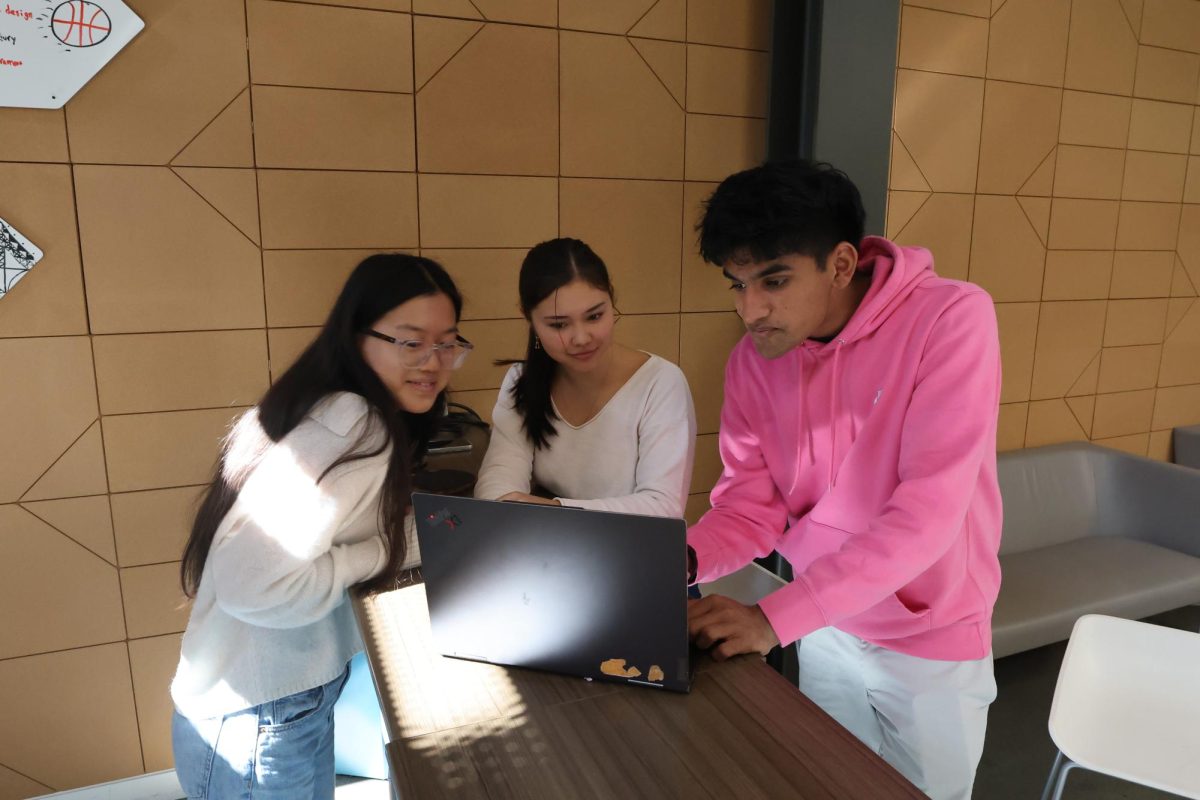

Both students and teachers discussed ways for the community to respond. Carroll encouraged the “responsible giving of resources, both material and financial, [and to] volunteer our time at the organizations [in our community].” Bennett Sweeney ‘27 emphasized the importance of awareness: “[because most of the people] here are very privileged,” they do not fully realize the extent to which these problems exist. The Urban Plunge was never intended to be a one-time service trip. It was meant to change students’ perspectives on poverty and how those in our community are affected by it. For juniors, seeing the issues firsthand made proposed federal cuts impossible to ignore. And for the SHP students who are often shielded from the realities of poverty, the plunge gave them a new perspective: that those in poverty are not just statistics on a class handout; they are men, women, and children who live in poverty and whose human dignity and survival depend on the help of the community and leaders.